采訪者:Denisa Tomkova

受訪者:朱發東 Zhu Fadong

1. Identity card work was inspired by the fact that people from other provinces need to apply for temporary resident card came when they want to come to Beijing. Could you explain it to me more though? Have you used it as a real ID or have you considered it as art?

您的作品 工作的靈感來自于一個事實,即從其他省份的人需要申請臨時居民卡來了,當他們要來北京。對於利用身分證這個既有的形式與格式,你有沒有把它作為一個真正的身份證或者您對於藝術的界定,以及藝術家角色的界定為何嗎?

沒錯,我的《身份證》作品靈感來自于中國大陸每個成年人都必須持有的身份證, 但更重要的是這個身份證所顯示的內容對應著后面的戶口信息。也就是說無論你現在是在北京、上海還是廣州等大城市,只要你出示身份證,馬上就會暴露你的戶籍,你不屬于你現在生活的這座城市,而要改變這一狀況,對于普通大眾來說,幾乎是不可能的。

Yes, my work “Identity Card” is inspired by the identity card that every grownup of Chinese mainland must hold, but what is more important is the household information it reveals. That is to say, whether you are now in big cities such as Beijing, Shanghai or Guangzhou, as long as you show your ID card, you will have your registered permanent residence exposed immediately. You don’t belong to this city where you are living. It’s nearly impossible to change this situation for ordinary people.

我的作品就是對這些不公與歧視的體制所做的回應。這是作為一個公民的回應,也是作為一個藝術家的回應!希望中國人也能享有遷徙自由,因為這只是一項最基本的人權!

My work is a response to this system of unfairness and prejudice. This is a response from me, as a citizen as well as an artist. I hope the Chinese can also enjoy the freedom of immigration for it is merely a basic human right!

2. Do you find the situation with identity cards still the same? If not what has changed?

你覺得在當今的情況下你是否會再創作同樣的作品? 你覺得關于的情況 在近些年是否還相同?如果不是,發生了什么變化?

可以肯定的是,在今天(當下)我肯定不會再創作這樣的作品了,倒不是今天的情況相比當時有什么變化或有什么好轉,其實恰恰相反。在現實面前,藝術顯得無能為力,甚至我的藝術觀念也很難讓更多的受眾知曉,藝術的圈子化或者說小范圍化,這一點和中國的互聯網很像,中國有互聯網么?回答是肯定的,但是不用我說,大家都知道,當然有總比沒有好。

One thing is certain, that is, I will stop creating such works now (at present). It is not because the situation now has changed or been improved. The fact is on the contrary. Art appears rather powerless before realities. It is also hard for my artistic concept to be known by more audiences. Art is limited to a circle or a small range, just like the Internet in China. Is there an Internet in China? The answer is yes. But needless to say, everyone knows the real situation. But, of course, it’s better to have access to than be completely blocked away from the Internet.

3. In the interview in 2010 you said that around 100 got identity cards, have there been any more people since then?

在2010年的采訪中你說,大約100人已經拿到身份證,目前2014年的情況如何? 是否也反應政策或是城鄉的差距?

這幾年幾乎沒有進展,這和我自己沒有像作品剛開始實施的頭幾年那么投入地去推廣有關(和什么政策,城鄉差距都沒有太大關系),因為作品經過1998—2000年幾年的推進后,我清楚地認識到在現實體制下,《身份證》這件作品只能是一件小范圍作品,而且作品所要傳遞的信息好像已不再被人關心,人們習以為常,在我看來非常嚴肅的問題在現在很多人看來好像是游戲一樣,當我意識到一件作品已經開始(或者已經)遠離我的初衷,那也就到了該結束的時候了。

There is almost no progress in recent years because I didn’t go all out to advertise my works in recent years just as what I did in the years my work was firstly implemented (It has nothing to do with policies or gap between urban and rural areas.). Through the dissemination from 1998 to 2000, I have clearly realized that under the current system, Identity Card can only be small-range work, and moreover, people seem to be less concerned about the messages my work reveals. They have been accustomed to it. A very serious issue to me has become a game to many people. When I realize that my work is starting to deviate from (or has already deviated from) my original purpose, it shall meet its end.

4. What does in general national identity card mean to you? Does it represent any political ideology to you?

對于你來說,身份證意味著什么?它是否代表了政治意識形態或是你對現有體制的看法?

對于我來說,身份證就意味著你沒有選擇。雖然一個人在什么地方被生下來,被什么人生下來,確實沒得選,確實是被動的。但是,當這個人成年以后,他(她)應該有權選擇是繼續留在出生地(父母所在地)還是選擇遷徙到其他地方去,影響或者左右這一選擇的只是個人的意志和個人對遷徙地的適應和生存能力,而不是其他諸如身份、戶籍等等。也就是這個國家的公民應該享有聯合國人權公約最基本的人權----人人享有遷徙自由。

To me, ID card means that you have no choice. It’s a fact that no one can choose where to be born or by whom to be born. It is a passive thing. But when he/she becomes a grownup, he/she should have the right to choose whether to go on staying at his/her birthplace (parents’ residential area) or to immigrate to another place. What influences or dominates such a choice can only be his/her personal will and adaptability to the resettled area, not other factors such as ID, registered permanent residence, etc. That is, the citizens in China should have the most fundamental human right endowed by the United Nations Human Rights Conventions – everyone should enjoy the freedom to immigrate.

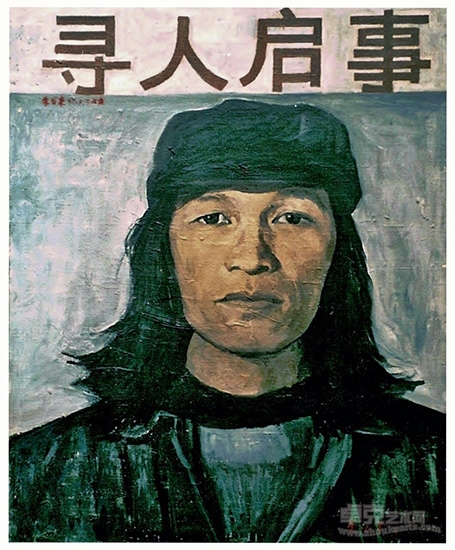

5. Your first performance was Looking for a Missing Person in 1993 and then Missing Person Announcement, 1993, This Person is For Sale (Negotiate Price on Spot). Before starting with performance you were practicing painting why did you shift to the performance art? When did you feel the need?

你的第一個行為藝術是1993年的 然后是Missing Person Announcement, 和 This Person is For Sale (Negotiate Price on Spot)。是什么讓你開始從油畫創作轉向了行為藝術的創作?你是什么時候感到這種轉變的需要的?

我從未想過要轉向。在我初涉藝術時,認識的藝術手段除了平面繪畫再就是傳統的雕塑了,對那個時期的我來說,雕塑可以說太遙不可及了,選擇繪畫是沒有選擇的選擇。1998年我只身去了海南島,在海南島的一年多里,無論是對我當時的生活還是對我以后的藝術歷程都產生了巨大的影響。在海南島海口市最初的一段時間,我每晚都住在地下室旅館,每晚2元錢,是那種一張床挨著一張床的過道,回去太晚就沒床位了。有一天我稍晚了一點,就沒住進去,后來只好在街上轉,還好海口很熱,夜晚也不冷,夜晚兩三點還是很多人,后來后半夜在一個水泥平臺上睡著了一會就天亮了,新的一天又開始了,原來居無定所,流落街頭也不過如此。我在海口的一年多,有很大一部分時間都是在街上轉悠,賣報紙、找工作、為報紙拉廣告、到汽車站等人口密集區為自己當時所工作的小旅店拉客源等等。在這一過程中,我感觸最深的就是滿大街的尋人啟事,電線桿上、旅館招待所、居民樓、辦公樓,甚至在大街上截住行人就問的,幾乎無處不在。其實我自己也是不辭而別來到海南島的,也是需要被尋找的人。

I have never thought of shifting. When I touched art in the beginning, I knew no artistic means other than flat drawing and traditional sculpture. To me at that time, learning sculpture is far beyond my reach, so I had to choose drawing. In 1998, I went alone to Hainan Island. I stayed there for more than one year, which had a profound influence upon not only my life at that time but also my artistic life later on. During my first days in Haikou City, Hainan Island, I had to stay at basement hotels for the night. Two yuan for each night. This sort of hotel is, in fact, an aisle with one bed closely placed to anther. If you came back too late, you would find all the beds had been occupied. Once, I came too late to stay at the hotel, so I had to wander in the streets. Luckily, it was hot in Haikou, not cold even at night. There were so many people even at two or three at night. I fell asleep against a cement platform in the latter half of that night. Soon the day broke and a new day began. The life of tramping the streets was nothing more than this. During the period of more than one year in Haikou, I spent a large amount of time wandering in the streets, selling newspapers, hunting jobs, distributing newspapers or soliciting guests for the hotel I worked with in the densely populated areas such as motor stations. During this process, what touched me most were notices for missing persons everywhere in the streets. They appeared on telegraph poles or inside hotels, residential buildings and office buildings. Sometimes, even the pedestrians in the streets were stopped for inquiry. These notices were everywhere. In fact, I myself came to Hainan Island without notifying others and could be counted as a person to be looked for.

1989年末,我回到云南,在海南的生活場景始終揮之不去,與此同時我也開始觀察我當時所生活的城市昆明,我驚奇地發現,昆明同樣充斥著尋人啟事和小廣告,我過去從來沒有注意到這些。我突然覺得我應該做點什么,這一次顯然任何平面的繪畫和雕塑都不可能表達我的感受,我想到了張貼尋人啟事小廣告,當時我已不在乎這件作品到底是繪畫、雕塑,還是其他什么了,反正就是能表達我的感受就足以。接下來是“尋人啟事”小廣告的內容,我猛然覺得那些在海南島以及在世界各地被親人朋友尋找的人,相對他(她)自己來說并沒有丟失,他(她)只是在自覺不自覺地滿世界找自己,正如我自己一樣。于是我決定尋找自己,只是讓我想不到的是,這一找就再也停不下來。

At the end of 1989, I came back to Yunnan. The life scenes of Hainan could not be erased from my mind. At the same time, I began to observe Kunming – the city where I lived at that time. To my surprise, I found it also filled with notices for missing persons and little ads. I had never noticed these before. Suddenly, I thought that I should do something. It was obvious that this time no flat drawing or sculpture could express my feelings. I thought of posting notices for missing persons or little ads. At that time, I didn’t mind whether this piece of work was a drawing, a sculpture or anything else. It was enough that it could express my feelings. Then I began to consider the contents of notices for missing persons. I suddenly felt that those being looked for at Hainan Island or in the rest of the world by their relatives and friends were, in fact, not lost to themselves. They were only looking for themselves everywhere in a conscious or subconscious way, just as what I was doing. Therefore, I decided to look for myself. What I didn’t expect was that I could not stop this process of seeking.

6. How would you describe your practice?

你會如何形容你的藝術主張或是有任何理論的實踐?你最終想要表達的是什么?

我一直認為藝術家僅僅是一個媒介,我一直尋求一種藝術與公眾的關系,當我身背“此人出售”廣告行走在大街上的時候,當我在公共場所張貼尋找我自己的 “尋人啟事”小廣告的時候,當我向別人推銷由我自己簽發的“身份證”的時候,我覺得此時藝術家自身已成為藝術的主體,成為媒介本身。藝術家的存在也許能給這個社會帶來一些新的可能性,或不確定性。至少能給一個忙于生計的社會提供一種幻想和漫無邊際的瞬間。

I have always been considering the artist as a medium. I have always been seeking a relationship between art and the public. When I wander with the “This Person Is for Sale” ad in the streets or seek my own “Looking for A Missing Person” in public places or promote to sell “Identity Card” issued by myself, I feel that the artist itself has become the main body of art and a medium. The existence of artists can provide this society with some new likelihoods or uncertainties. Or at least, it can provide this bustling society with a momentary and boundless fantasy.

7. Do you think art has a capacity to stimulate the discussion in the society? Comparing with two to three decades ago, what’s your opinion on the Chinese art now? What are the challenges and predicament for the contemporary Chinese artists, in your opinion?

你認為藝術有能力激發社會的討論嗎?您對於目前中國藝壇的現況,今昔之比,有什麼評價與看法?您認為對於中國當代藝術家有哪些挑戰與困境?

不能,好的藝術通常是唱反調的,不合作,挑刺,你說往西他要往東,甚至有時是“猥瑣”的。這些都和主流社會所倡導的所謂正能量、歌舞升平、齊心合力、萬眾一心之類的假象格格不入。對于目前中國的藝術現況,如果是和1990年代比,今天的藝術顯得平和而多元,但也少了一些發自內心的沖動,很難看到刻骨銘心和“不管不顧”的作品。

No, it can’t. A good art form usually strikes up a discordant tune or adopts an uncooperative or faultfinding attitude. It is always doing the contrary. And sometimes, it can even be considered “obscene”. All these are incompatible with the false appearances advocated by the mainstream society such as positive energy, singing and dancing in celebration of peace or making concerted efforts. As far as the status quo of China’s art is concerned, today’s art appears peaceful and multi-elemental compared with that of 1990s. However, it lacks the impulse from one’s inner world. The impressive and “desperate” works are rare to be seen.

對于中國當代藝術家所面臨的挑戰與困境,我現在覺得這個問題不太成立,因為今天雖然不能說已經完全全球化了,但你中有我,我中有你的現實已是不可爭辯的事實,也就是說大家所面對的挑戰與困境幾乎都是一樣的。如果一定要說中國藝術家所面臨的挑戰與困境有什么不同之處,那就是如果西方國家的藝術家揮拳打出去,無論怎么使勁,結果無一例外地都像是打在了棉花上,而中國藝術家只要卯足了勁,就一定能打在實實在在的墻上。

As to the challenges and plights which the Chinese contemporary artists are facing, I don’t think it to be a tenable issue. Though the complete globalization hasn’t been achieved yet, you can never deny the “me in you and you in me” situation. That is to say, the challenges and plights all men face are almost the same. If I have to identify the unique challenges and plights the Chinese artists are facing, I can say that if a Western artist shakes his fist with whatever strength, the result is, without exception, like striking the cotton; however, as long as a Chinese artist musters all his strength, he is sure to strike the solid wall.

8. In regard to your work VISA, you talked about the difficult situation as a Chinese traveling to the Western countries. Do you find the topic of identity cards and situations on VISAs and the tightened immigration policies reinforced by Western countries (mainly Europe and North America) somehow could be relevant? Why are you interested in political and migration related topics? When you work on pieces like ‘Identity Card’, do you have any art market or buyers in mind, or they are not your concern?

關于你談到出國時的工作簽證的情況時,作為一個中國人你旅行到西方國家,身份證和簽證的話題主題是否相關?為什么您對於這些政治與移民的主題發生興趣?@腌您創作像身分證或是其他有爭議性政治性作品時,是否也曾考慮過市場?或者買家與市場不是您的主要考量了?

當然相關,因為作為一個中國人,你到西方國家是必須簽證的,當你費好大的勁終于獲得了簽證,別高興太早,當你入境時,因為你的中國護照,時常還要受到特殊對待,長時間的盤問,拿著你的簽證左看右看,好像簽證不是他們大使館簽發的。

Of course, they are relevant. As a Chinese, you must get a visa if you want to go to a Western country. But when you get your visa through great efforts, it will be too early for you to relax. When you are entering their country, you will be specially treated for your Chinese passport. They will inquire you for a long time and carefully check your visa as if it were not issued by their embassy.

說到我為什么對于政治與移民問題發生興趣,在此我想表明一下,在我看來這些問題其實也是藝術問題。不是我對這些問題發生興趣,而是這些問題無時不對我的生活和藝術造成影響,上個網也只能是他們想讓你看到的,有時網上“干凈”到連一個裸露的乳房都看不到。出國辦展覽作品可能被扣,人可能被拒簽。我不喜歡四平八穩,不疼不癢的作品,至于是否考慮市場的問題,我想說在1990年代初根本就沒有什么市場,更談不上考慮市場的問題了。

As to why I am interested in politics and issue of immigration, I have to say that these things are in fact an artistic issue. It’s not that I become interested with these things, but that these things are affecting my life and art career all the time. On the Internet, you can see nothing more than what they wish you to see. Sometimes, it is so “clean” that you can’t find a naked breast. If you want to hold an exhibition abroad, your works may be deducted or you can’t obtain a visa. I do not like methodical and well-balanced works. As to considering the issue of markets, I want to say that there were almost no markets in the early 1990s, let alone considering the issue of markets.

9. Your artworks Identity card as well as Looking for a Missing Person and This Person is For Sale seem quite political to me, like kind of revolt against something. Is it correct? If yes can you tell me more about it please?

你的作品Identity card,Looking for a Missing Person 和This Person is For Sale 在我看來極具政治意味,它們好像在反抗著什么。我是否可以這樣理解?如果是的話,你能告訴我更多關于它們的信息嗎?還是這代表您對變遷中的中國社會的看法?

可以這么理解,我不太喜歡向別人解讀我的作品,更不會談及所謂創作動機等問題,因為它們就沒有動機,我不希望我的解釋影響觀眾或或讀者對我作品的解讀。

It can be so interpreted. I don’t like my work being illustrated and I am more unwilling to talk about the so-called creative motives. There are no motives at all. I don’t hope that my explanation will influence the interpretation of my audiences or readers of my works.

10. When many contemporary Chinese artists tend to stress on ‘ Chineseness’ and ‘Chinese Identity’ and ‘Chinese elements’ for their art to cater for the market, what’s your view on this? Would you tend to choose a global issue to suit the fashion of globalization and for exhibition

works abroad? What are the challenges you encounter when exhibiting works for international audience, and how are they different from domestic audience in China?

當許多當代藝術家都使用中國式的符號以適應現今的藝術市場,您對於此現象有如此看法?您會比較傾向去中國化來達成全球性藝術?還是在選取題材上,你會傾向選取全球性議題作考量,以作為到國外展覽所需?您認為國內跟國位展覽有什麼不同與挑戰嘛?

對于中國式符號的使用,我覺得無所謂,無可厚非,歐美藝術家也有使用中國符號的,近年來好萊塢也常使用中國元素,各有各的目的。我自己在創作前不會刻意去想什么中國化還是全球性這些問題,我還是更注重跟隨自己的內心,一定是我感興趣和關注的主題樣式才會被創作出來。我想作為這個世界上的一個人,我肯定和這個世界是關聯的,這是一個人活著的證據,那么我感興趣和關注的主題樣式肯定會得到其他人的共鳴,關注和喜歡,只是人數多少的問題。對藝術家來說,藝術就是一場賭注,好的藝術家都是真正的賭徒,對于賭徒來說哪的賭場都一樣。

I don’t mind using Chinese elements. There is nothing wrong. Some European and American artists are also using Chinese elements, and even Hollywood are using Chinese elements in recent years. They have different purposes. I won’t deliberately consider issues such as “Chineseness” or “globalization” before creating. I pay more attention to my inner heart. Only those topic forms that I’m interested in and concerned about will be created. As a human in this world, I’m sure to be linked with this world. This is the evidence that a man is living. Then the topic forms that I’m interested in and concerned about will surely evoke resonances, concerns and good feelings in others, though the number of people being evoked is uncertain. To an artist, art is like a gambling. A good artist is a real gambler. And to a gambler, he can gamble in any gambling house.

皖公網安備 34010402700602號

皖公網安備 34010402700602號